Invisible Children

Invisible Children

Project Statement

This work started in 2014. The refugee problem had not yet reached the magnitude it eventually reached in Europe, nor was it all over the news at all times, but in Lebanon, it had quietly started.

Lebanon is a country of about 4 million people and in 2014 there were about 1.5 million Syrian refugees. Straddled by a weak economy, and domestic political tensions, Lebanon was finding it hard to cope with the large influx of refugees inside its borders, their presence creating increased internal tension and divisions within the already fragile country, and therefore making the humanitarian crisis an even more difficult one to resolve.

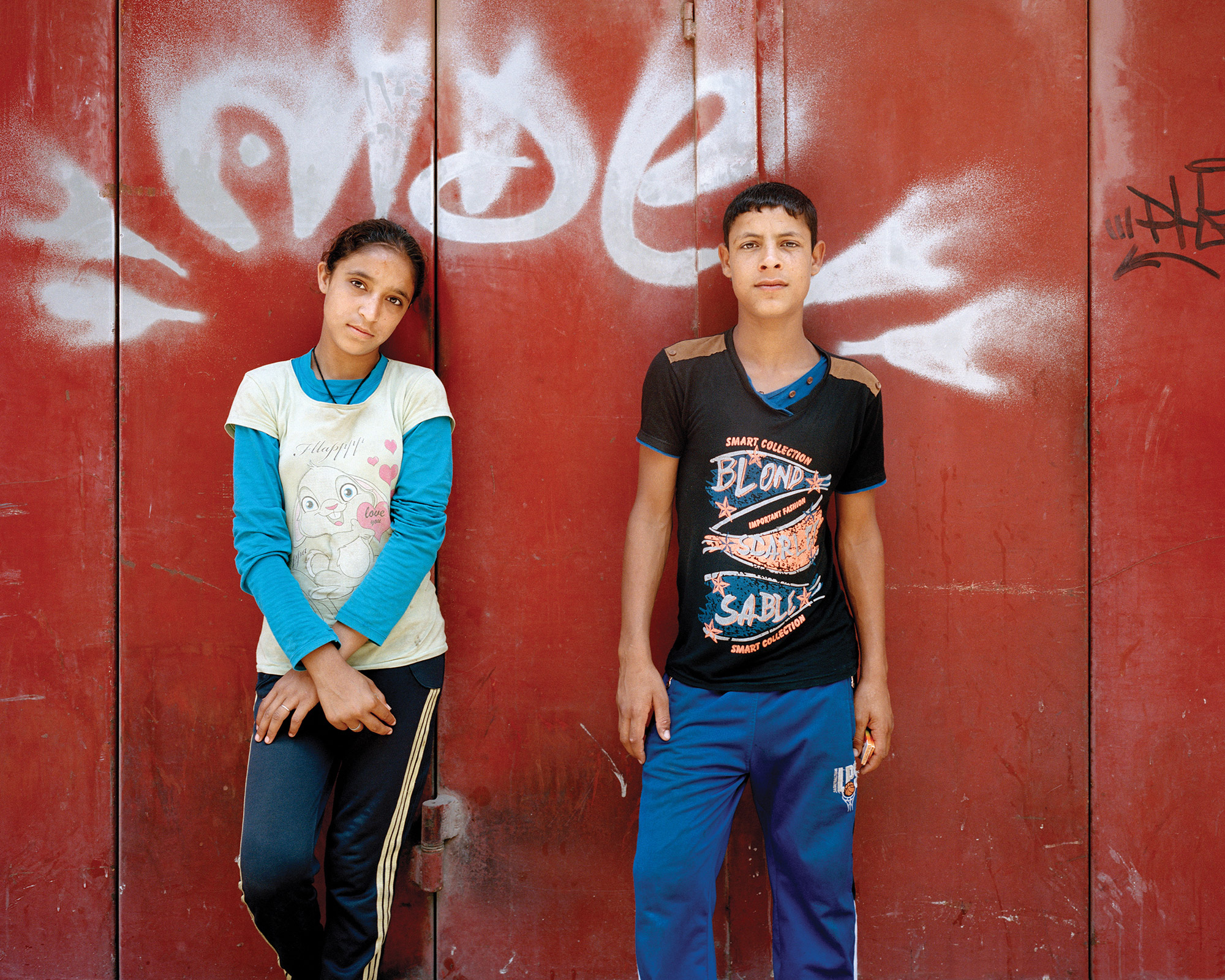

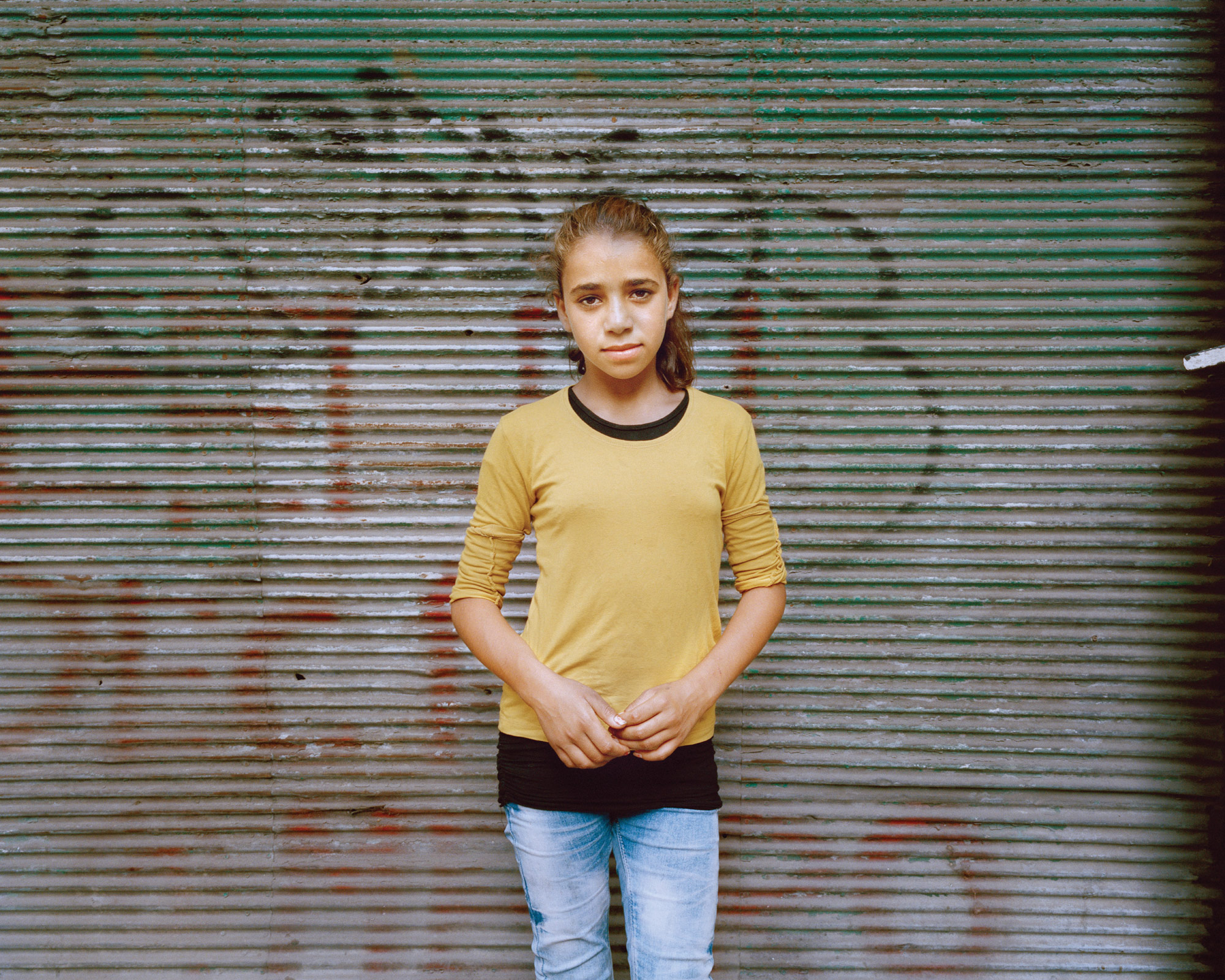

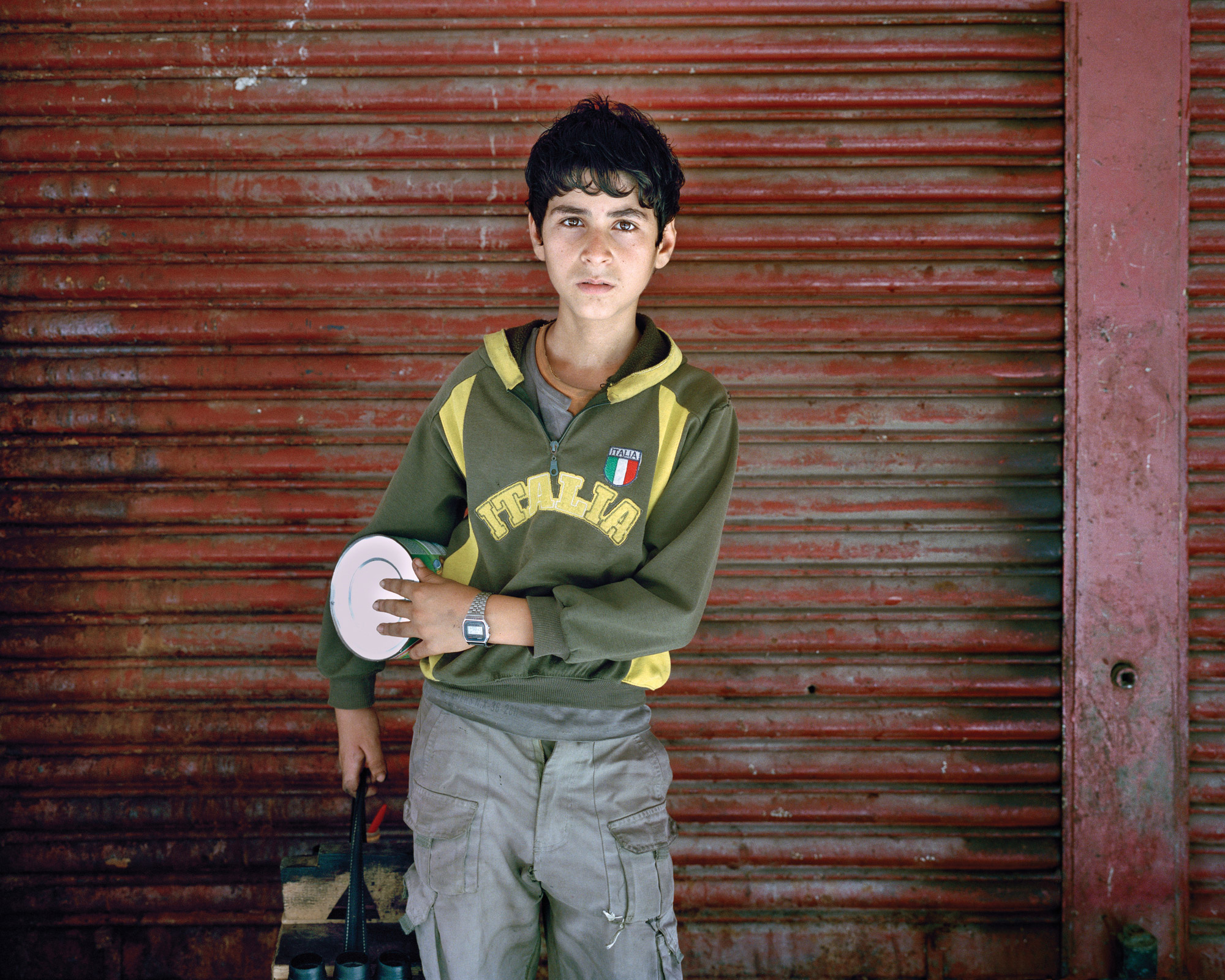

However, when I was in Beirut in the summer of 2014, I was poignantly struck by the Syrian refugee children and teens standing at every other street corner, most often begging for money, sometimes selling red roses or miscellaneous trinkets, or carrying beat-up shoe-shining equipment. They all said they were working. They were being brought by the truckload every morning, dropped off on the streets and expected to bring money back every day. People often walked or drove by them seemingly indifferent or just fed-up by what the influx of refugees has done to the country’s economy and resources and by what the city had become with kids begging in most cosmopolitan areas of Beirut.

I spoke to the kids and quickly realized that their stories were eerily similar: they were in Lebanon with their mothers living in makeshift homes; their fathers had either died or were fighting in Syria – they never knew which side he was fighting on; they were not at school; they were living in a temporary limbo that was becoming more permanent by the day; many couldn’t read or write, and they were all nervous and scared and often gave me fake names.

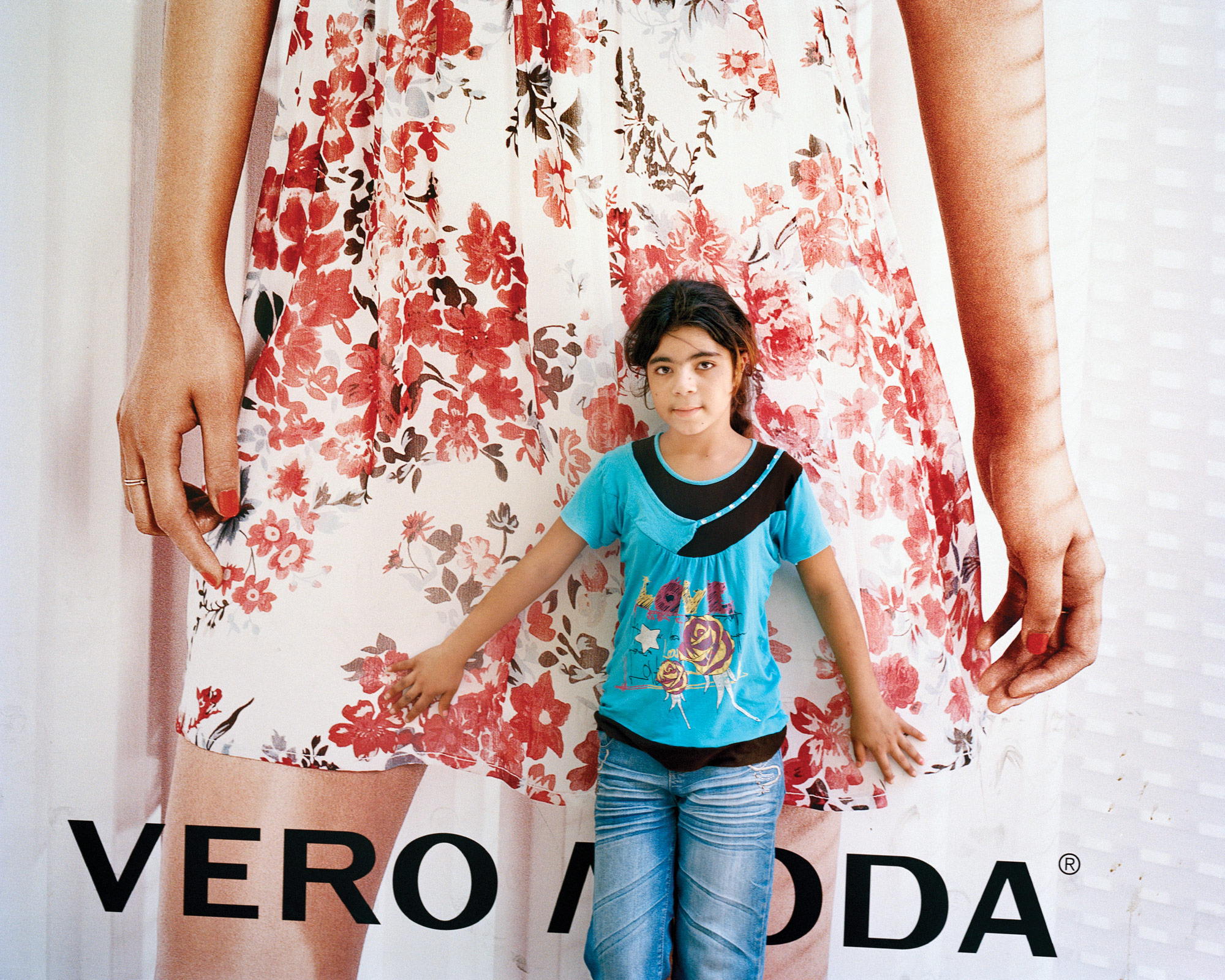

As a mother of similar age children, I was truly moved by these kids, struck by the fact that they had become almost faceless and invisible. They seemed to blend with the graffiti in front of which they were standing, like an added new layer of history, of ripped billboard advertising, as invisible and as anonymous. Being perceived as “the refugees,” the group identity seemed to define them more than their individual identity. Maybe by keeping them individually anonymous, one can more easily ignore the magnitude of the refugee crisis.

I tried through my images to put an individual face to the invisible children, to give them their dignity and portray their individuality. I eventually added to the series a few images of another set of refugees, of invisible children: third generation refugee girls in Palestinian refugee camps.